Over the last few years I’ve been watching my way through some of the non-Johnny Weissmuller “Tarzan” films. This started with a deep dive into Gordon Scott’s work and has continued into Mike Henry’s tenure and friends, I’ve been having a blast.

Thinking back, my experience with Mike Henry’s work probably goes back to a little film called Skyjacked from 1972. I have a shameful sweet spot in my heart for “airplane in trouble” movies and Skyjacked (which features Henry as a co-pilot!) is among my favorites in this dated and occasionally silly subgenera.

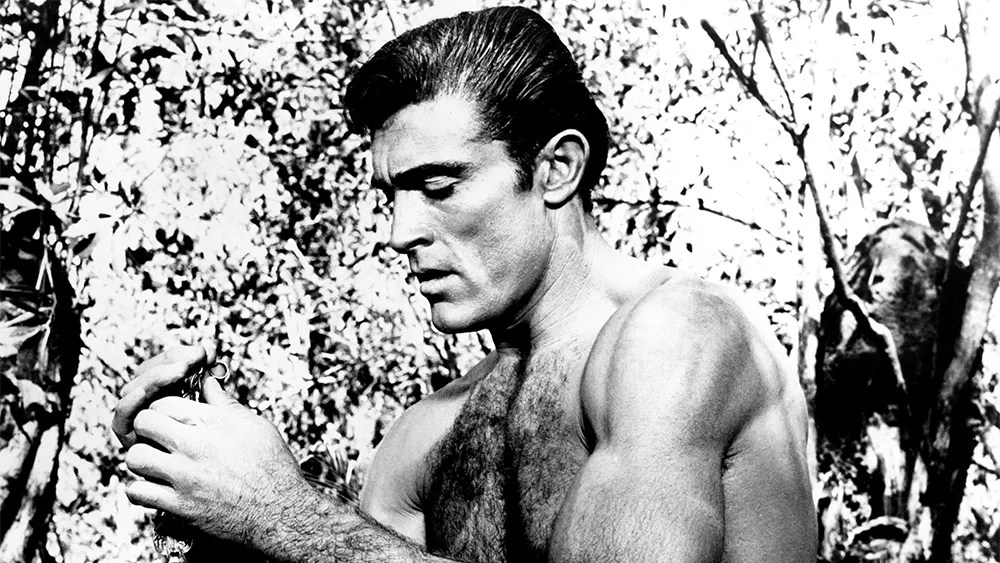

For those who might not be so familiar, Mike Henry stepped into the famous Tarzan loincloth for three films beginning in 1966 with Tarzan and the Valley of Gold and ending with 1968’s Tarzan and the Jungle Boy.

Looking at Tarzan’s history on film, things were slowing down by this point. Henry’s films would lead into the late 1960s television show… a bit more on this later. However, once the series ended, Tarzan wouldn’t be seen on-screen again until the 1980s. Every franchise needs a break at some point.

I suppose, this one probably needed one in the 1960s. It was ready. Tarzan had been a fixture on the silver screen almost yearly since Tarzan the Ape Man premiered in 1932. Heck, this isn’t even factoring in the silent films and serials going back as far as 1918 when Elmo Lincoln played the titualar role.

Returning to the 1960s though Mike Henry is perhaps best known to some thanks to his football career. Before he was an actor, he strapped on the cleats as a linebacker for the Steelers and later the Rams between 1959 and 1964.

Looking at his IMDB page, Henry’s acting career started in earnest. We’re talking very earnest. He’s billed as “Big Guy” in a 1963 episode of The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet. Later, he’s listed as playing an uncredited role in Palm Springs Weekend. He’s credited as “Doorman” the same year. Henry’s casting as Tarzan is, in truth, his breakout.

An interview in The Daily Breeze dated July 23, 1966 takes great pains emphasize just how modern Henry’s Tarzan is. This is a Tarzan for the James Bond era. Henry is quoted, “There is an audience cynicism involved with heroes today… my Tarzan believes in fighting evil in any way he can. When I kill them, they’re dead”.

This hits straight at one of the most interesting facets in (so far) two of Henry’s three Tarzan outings. It barely needs to be said that spies were hot in the middle of the 1960s. Dozens of television shows and movies sprung to life in the wake of James Bond’s 1962 cinematic debut.

While there’d been “intelligent” Tarzans before, Mike Henry’s Tarzan feels like The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Tarzan had a baby… and it is as strange a thought as it sounds.

This version of the character isn’t living in a jungle treehouse clad only in a loincloth. Don’t get me wrong, he finds the loincloth! It just takes a little bit. He begins the film in a suit, a well-tailored suit.

I was left deeply reminded of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. as I watched the opening of the first two films. Henry’s Tarzan doesn’t have a “Bond” budget. These are a little smaller and a little more restrained. It’s not that they aren’t cool… they’re just “TV cool”.

Interestingly, “TV cool” makes sense. A dive into the series’ history shows that producer Sy Weintraub was anxiously looking to move Tarzan onto the small screen. Some might remember that Ron Ely eventually stepped into the famous loincloth in 1966 when Tarzan premiered on NBC for a two season run.

A brief look over newspapers of the time reveals that Mike Henry was actually supposed to helm the TV show as well. However, it becomes clear by the fall of 1966, for Henry the bloom was off the rose. Henry was done playing Tarzan. He was over it.

A Los Angeles Times article dated October 23, 1966 goes into some detail:

“In the case of Mike Henry, the ex-football pro who made the last three Tarzan films was supposed to be the TV Tarzan, there is much bad blood between him and Sy Weintraub, the Tarzan producer…. Mike has sued Sy three times, the last one being for a $75,000 bite which Mike says Cheetah the Chimp bit his cheek.”

The $75,000 bite is well documented in newspaper coverage going back to 1965. An October 25, 1965 article in the Los Angeles Times describes Cheetah “sinking her teeth” into Henry’s chin while filming Tarzan and The Great River. Henry reportedly missed a week of shooting to recover after what a December 2, 1965 article in the Daily-News Post reported was 18 stitches in his face.

Surprisingly, a July 23, 1966 article in the Daily Breeze turns the incident into a bit of a joke, writing, “‘The chimp was bitter over billing,” Henry kidded. “Actually… the scar makes my face look lived in”’. The same article goes on to mention that Henry also suffered serious bouts of food poisoning four times during the shoot. Apparently, a Tarzan shoot is not for the faint of heart.

Ultimately, a look over Mike Henry’s filmography shows us that television was by far and away his bread and butter. However, he jumped into another well-remembered film franchise in 1977 playing Junior in Smokey and The Bandit. Henry would return for the series’ second and third installments in 1980 and 1983. The role is, admittedly, as much, if not more discussed than his time as Tarzan.

Henry continued acting steadily until 1988 when, according to his 2021 Variety obituary, his heath forced him to retire.

Mike Henry passed away in 2021.

Tarzan and the Great River

At this point in my movie viewing, I’ve seen two of the three Mike Henry Tarzan films with Tarzan and the Jungle Boy still eluding me. The three films were, impressively, shot one right after the other. If you know where to find Tarzan and the Jungle Boy, call it out. It’s quickly becoming a white whale cinematic quest. I have to finish this series.

Tarzan and The Great River find the titular jungle man (Henry) trying to help inoculate the native indigenous populations against an impending epidemic. However, things are complicated by a cult like tribe threatening to enslave the local people. Jan Murray, Manuel Padilla Jr., Diana Millay and Rafer Johnson co-star in the movie. Robert Day directs the film from a script by Bob Barbash.

Much of Tarzan and the Great River revolves around Tarzan teaming up with a ship captain (Jan Murray) and his young charge (Manuel Padilla Jr) to help them get down the river. This is, at its heart, a jungle quest.

Tarzan films are inherently challenging, especially when viewed through a 2025 perspective. These films harken back, often directly, to Edgar Rice Burroughs’ original works. Let’s remember, the first Tarzan novel, Tarzan of the Apes was initially published in 1912.

There’s a ton of politics, pith helmets and colonization in these movies… then there’s the often uncomfortable racial politics that come with it. Hollywood Central Casting and its resulting struggles were still very much in practice at this point. Though truthfully, even in 1967 these films feel like action relics. While they’re trying to be a “Jungle James Bond” these end up settling for a gentle “Dad movie” nostalgia.

Director Robert Day comes to the film with a lot of Tarzan experience. He’s billed as the director on not only the first two Mike Henry efforts, but also Tarzan’s Three Challenges (1963) and Tarzan the Magnificent (1960) staring Jock Mahoney and Gordon Scott respectively.

As such, Day easily captures the wilderness photography. Tarzan and the Great River doesn’t struggle with its exotic locations and the dangerous animal footage. In fact, it largely avoids falling into the “stock footage” trap that so often snares adventure films during this era. This doesn’t scream travelogue. It actually feels like the cast is there!

Looking at period reviews, critics of the time were realistic and often hit the second installment right on the head.

This movie is at its best when it’s being light and fun. Speaking bluntly? It’s a kids movie. The Los Angeles Times writes in its September 15, 1967 review, “…this well made movie, which has some beautiful scenery, is just right for the 12 year old mind, but is likely to bore anyone above that level.”

With that being said, Manuel Padilla Jr (who was just about 10 years old at the time) is certainly a bright spot in the film. In fact, he fits so well that he would rejoin the Tarzan team for the 1966 TV series.

The youngster has the challenging task of playing off (the always delightful) Jan Murray for a good chunk of the film. However, the two tap into fun and easy chemistry.

At the same time though, Padilla is the perfect person through which to view this movie. There’s a magic to the action when viewed through his childlike eyes. His fascination with Tarzan and all the animals is actually a bit infectious. It’s fun being in this youngster’s world. This is who Tarzan is really for.

Ultimately though, like the Times reported, it’s hard to connect with Tarzan and The Great River‘s magic, unless you’re 10 years old. There’s solid wilderness photography, plenty of fiesty animals and entertaining performances, but there’s something here that didn’t quite gel for me.

As I come to the end of this piece, this honestly proving to be a hard franchise to talk about. Tarzan isn’t just Mike Henry, Jock Mahoney or Johnny Weissmuller. It’s bigger than one man. And, to be frank, while I can’t say these Henry films “gelled” for me, I also didn’t “dislike” them either. I had a blast.

If history has shown us anything, franchises shift. They flow and sometimes, they drift a bit. This is where Tarzan was in the 1960s. It was on a meander point in the river. Those looking for the mighty call of Johnny Weissmuller might find themselves disappointed, but Henry’s tenure feels like a strangely timely point in its history. The King of the Jungle may have been struggling with his identity, but in this movie’s gently quirky 1960s imagery, it’s a heck of a lot of fun.

Leave a comment